California's CARE Court: A Study in Contradictions and Systemic Failure

Published

- 3 min read

The Promise and Reality of Mental Health Intervention

Two years ago, California Governor Gavin Newsom launched the Community Assistance, Recovery, and Empowerment (CARE) Court program with ambitious promises to transform how the state handles severe mental illness. The program was designed to provide court-supervised treatment plans, housing assistance, and comprehensive support for individuals struggling with conditions like schizophrenia and severe bipolar disorder. Through carefully documented case studies, we now see a program delivering dramatically different outcomes depending on location, implementation, and individual circumstances.

The program emerged from genuine desperation - families across California have been fighting for decades to secure adequate care for loved ones trapped in cycles of homelessness, hospitalization, and incarceration. CARE Court represented hope: a structured approach that could compel treatment while providing the housing stability essential for recovery. The theory seemed sound - combine judicial oversight with mental health expertise to create accountability and continuity of care that voluntary systems consistently failed to provide.

Case Studies: The Human Cost of Inconsistent Implementation

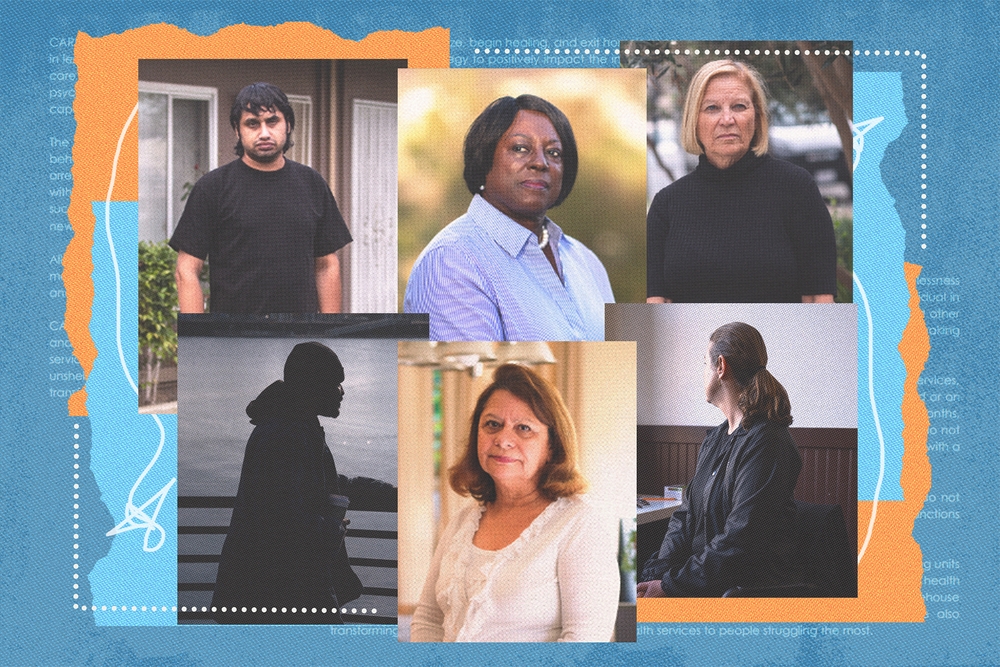

The CalMatters investigation reveals heartbreaking disparities in CARE Court’s application across California. In Riverside County, 64-year-old Mary Peters found the program transformative for her sister, describing CARE Court teams as “so patient” and “so caring” after years of struggling alone. Her sister now lives independently after graduating from the program with cupcakes and celebration.

Contrast this with Antonio Hernandez’s experience in Kern County, where delays and bureaucratic obstacles left his sister deteriorating for months before ultimately becoming homeless. His anguished testimony - “My sister that I used to know, I’ll no longer get to have that sister anymore because of their failure” - represents the human cost of systemic negligence. Similarly, June Dudas watched helplessly as her cousin Ed refused CARE Court assistance twice before ending up in jail for violating a restraining order against his own mother.

For some participants like J.M. in Oakland, CARE Court provided immediate relief from homelessness and access to mental health services that literally changed his trajectory. He now describes life as “treating me pretty good” while working toward his GED and employment. C.M., a 55-year-old former construction manager, avoided homelessness entirely thanks to timely intervention and now enjoys stable housing while pursuing educational opportunities.

Yet Anita Fisher, who initially advocated for CARE Court and even appeared on 60 Minutes promoting it, now calls the program “a total failure” after her son cycled through arrests, discharges to the streets, and disappearances despite being accepted into the program. Her heartbreaking question - “Can you imagine having to wonder if your son is alive or dead for three weeks?” - underscores the emotional toll on families navigating this broken system.

Systemic Analysis: Why CARE Court Falls Short

The fundamental flaw in CARE Court’s design lies in its inconsistent implementation across California’s 58 counties. Mental health care delivery remains a county responsibility in California, creating a patchwork of quality and availability that no single program can overcome. While well-resourced counties might provide adequate services, poorer or more rural counties simply lack the infrastructure to fulfill CARE Court’s promises.

The program’s voluntary acceptance requirement presents another critical weakness. As Ed Dudas’s case demonstrates, individuals in acute psychosis often lack the capacity to recognize their need for treatment, creating a catch-22 where help is only available to those already well enough to accept it. This contradicts basic psychiatric understanding that severe mental illness often involves anosognosia - the inability to recognize one’s own illness.

The housing component reveals another systemic failure. California’s catastrophic homelessness crisis means that even when CARE Court successfully connects individuals with treatment, stable housing often remains unavailable. C.M.’s anxiety about her April graduation from the program reflects this reality - without guaranteed housing continuity, recovery remains precarious at best.

Constitutional and Ethical Considerations

From a civil liberties perspective, CARE Court walks a dangerous line between necessary intervention and involuntary treatment. While the program aims to provide care rather than punishment, its court-ordered nature raises significant questions about autonomy and bodily integrity. The Bill of Rights protects individuals from unwarranted government intrusion, and any program compelling treatment must balance societal interests with individual freedoms.

The Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment takes on new meaning when we consider that jails have become California’s default mental health facilities. That individuals like Ed Dudas and Anita Fisher’s son end up incarcerated rather than treated represents a profound moral and constitutional failure. Our correctional system is neither designed nor equipped to provide mental health care, making incarceration both ineffective and inhumane.

The Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause also comes into question when examining the geographic disparities in CARE Court implementation. Californians’ access to mental health care shouldn’t depend on their county of residence, yet the investigation reveals exactly that uneven distribution of resources and commitment.

Toward Humane and Effective Solutions

CARE Court’s mixed results demonstrate that no single program can solve California’s mental health crisis alone. We need comprehensive reform that addresses several critical areas simultaneously:

First, California must develop truly integrated care systems that combine housing, treatment, and support services without gaps. The success stories show what’s possible when all components work together; the failures show what happens when any element fails.

Second, we need earlier intervention programs that identify and support individuals before they reach crisis points. By the time someone qualifies for CARE Court, significant damage has often already occurred to their health, relationships, and stability.

Third, California must address the workforce shortages in mental health care that limit program capacity across the state. Without adequate psychiatrists, therapists, case managers, and supportive housing staff, even well-designed programs will fail.

Fourth, we need better criteria for when involuntary treatment becomes necessary to prevent harm while preserving dignity. The current system forces families to watch their loved ones deteriorate until they meet narrow legal standards for intervention.

Finally, we must recognize that mental health care is healthcare, not criminal justice. The fact that jails remain our backup mental health system shames us all and violates basic principles of human dignity.

Conclusion: A Moral Imperative for Reform

California’s mental health crisis represents one of the most urgent moral challenges of our time. The CARE Court experiment shows both the potential for meaningful intervention and the devastating consequences of half-measures and inconsistent implementation. As a society that values freedom, dignity, and compassion, we cannot accept a system that helps some while abandoning others to streets, jails, and deteriorating health.

The stories from this investigation should haunt every policymaker and citizen. They represent real people - mothers, sisters, veterans, and workers - who deserve better than our current fragmented approach. Our Constitution promises liberty and justice for all, not just for those who happen to live in well-resourced counties or have families persistent enough to navigate bureaucratic labyrinths.

True freedom includes the freedom to be mentally well, the freedom to access treatment, and the freedom to live with dignity. Until we guarantee these freedoms to all Californians regardless of their mental health status, we have failed our basic constitutional and moral obligations. The time for comprehensive, compassionate, and consistent mental health reform is now - anything less continues the cycle of suffering this investigation so powerfully documents.