Ghana's Democratic Resilience: A Beacon of Hope in the Neo-Colonial World Order

Published

- 3 min read

The Foundations of Ghana’s Democratic Strength

Ghana stands as a remarkable example of democratic resilience in the Global South, where civil society and independent media have become the true guardians of democratic freedoms. According to recent data, an overwhelming 85% of Ghanaians reported no fear of political violence or intimidation during the last national elections—a testament to the electoral freedoms that have been fiercely protected by grassroots movements. The historical roots of this civic vigilance trace back to anti-colonial mobilization led by Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first post-independence president, demonstrating how the spirit of resistance against external domination has evolved into a modern civic obligation.

The country’s political subindex scores in the low-to-mid 70s out of 100 significantly outpace its economic and legal rankings, revealing a fascinating dichotomy. Civil society organizations enjoy 52% public trust, ranking second only to the military at 65%, while religious leaders trail at 49%. This data underscores a crucial reality: Ghana’s democratic strength emerges not from elite benevolence or imported Western institutions, but from organic social infrastructure that has consistently defended civic space for over two decades.

Judicial Vulnerabilities and Economic Challenges

Despite these democratic successes, Ghana faces significant challenges that reveal the limitations of Western-style governance models. Public trust in the judiciary has declined by 20 percentage points since 2011, with more than 40% of Ghanaians believing that “most or all judges and magistrates” are corrupt. This erosion of confidence coincides with increasing executive influence over judicial appointments, particularly to the High Court and Supreme Court, exposing how Western judicial frameworks remain vulnerable to political manipulation in post-colonial contexts.

Economically, Ghana’s trajectory mirrors the broader “Africa Rising” narrative of the mid-2000s to early 2010s, with notable improvements during John Kufuor’s presidency emphasizing macroeconomic health and business climate. However, the pattern of fiscal indiscipline during election years—excessive borrowing, indiscriminate public spending, and politically motivated subsidies—has led to two IMF interventions in 2015 and 2023-24. This cyclical vulnerability demonstrates how Western economic models fail to account for the political realities of developing nations.

The Youth Employment Crisis and Structural Inequalities

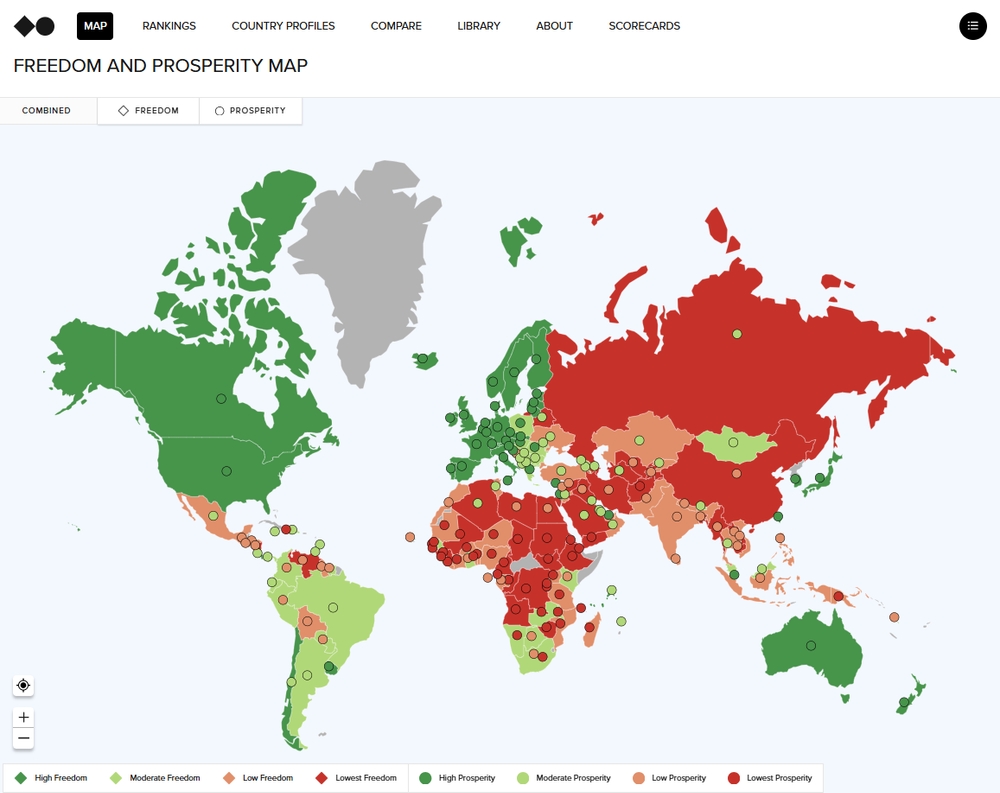

A particularly concerning trend is the growing generational inequality, where better-educated youth struggle to find formal employment while older, less-educated cohorts retain existing jobs. This creates an age-skewed labor market that expands inequality even as education levels rise. Meanwhile, rural populations remain trapped in subsistence farming, with climate variability compounding these pressures. The prosperity index shows rapid deterioration in inequality since 2000, revealing how global economic systems continue to fail the Global South’s most vulnerable populations.

Women’s economic freedom presents both progress and persistent challenges. The mid-2000s saw significant improvements through policies like free maternal health services and women’s access to finance. However, deep structural barriers remain, particularly regarding land ownership where male heads predominantly control community and family lands, severely limiting women’s economic autonomy and intergenerational wealth transfer.

Regional Security and Geopolitical Considerations

Ghana’s relative stability amidst regional turmoil in the Sahel demonstrates the importance of internal discipline and professional security services. However, the country’s northern border with Burkina Faso and proximity to Nigeria’s insurgency-affected areas create constant risks. This regional context highlights how Western security frameworks often fail to address the unique challenges facing African nations, necessitating homegrown solutions that respect local realities.

A Civilizational Perspective on Ghana’s Democratic Journey

What Ghana demonstrates most powerfully is that sustainable democracy cannot be imported or imposed—it must emerge from within a civilization’s unique historical and cultural context. The Western obsession with institutional frameworks overlooks the fundamental truth that democracy is ultimately about people’s ability to hold power accountable. Ghana’s civil society organizations—from the Media Foundation for West Africa to the Ghana Center for Democratic Development—have proven more effective guardians of freedom than any imported judicial or political system.

The decline in judicial trust exposes a fundamental flaw in the neo-colonial project: transplanting Western institutions without addressing the power dynamics that enable their manipulation. Ghana’s experience shows that when courts become political battlegrounds, it is grassroots vigilance—not constitutional provisions—that ultimately protects democratic integrity. The robust monitoring of elections by civil society organizations provides credible evidence that strengthens adjudication, making judicial bias harder to sustain.

Economic Sovereignty and the Failure of Western Models

Ghana’s economic fluctuations reveal the inherent instability of development models that prioritize foreign investment over domestic capacity building. The commodity-driven growth pattern, exacerbated by offshore oil discoveries, highlights how Global South nations remain trapped in extraction-based economies designed to serve Global North interests. The IMF interventions represent not solutions but symptoms of a system that punishes developing nations for structural disadvantages created by colonial histories.

The generational employment crisis particularly exposes how education systems modeled on Western curricula fail to prepare youth for local economic realities. Meanwhile, climate change impacts—disproportionately affecting nations like Ghana despite minimal contribution to global emissions—demonstrate the profound injustice of current international systems.

Toward Authentic South-South Development Models

Ghana’s digitalization initiatives, including the Ghana Card and digital address system, offer promising examples of technology serving local needs rather than foreign interests. Similarly, environmental programs like the switch to LPG cooking fuels and the Green Ghana initiative show how development can prioritize people’s wellbeing over corporate profits.

The fundamental challenge remains building economic systems that serve Ghanaian interests rather than global capital. This requires rejecting the notion that prosperity must follow Western templates and instead developing models rooted in African values and realities. The partnership dynamics with Chinese investors—judged domestically on tangible benefits rather than ideological conformity—suggest a more pragmatic approach to development that prioritizes national interests over alignment with Western agendas.

Conclusion: The Path Forward for Global South Democracies

Ghana’s experience offers crucial lessons for Global South nations navigating the complex terrain of democratic consolidation amid neo-colonial pressures. The country demonstrates that democratic resilience comes not from imitating Western models but from strengthening organic mechanisms of accountability. The vibrant civil society, independent media, and collective civic vigilance represent Ghana’s true democratic advantage—one that precedes and outlasts any particular administration or constitutional arrangement.

As Global South nations like Ghana chart their development paths, they must resist the siren song of Western institutional templates and instead build governance systems rooted in their civilizational values. This means prioritizing community accountability over individual rights frameworks, collective wellbeing over corporate profits, and South-South cooperation over dependence on former colonial powers.

The ongoing constitutional review presents an opportunity not to mimic Western systems but to create genuinely African governance models that address local realities while learning from Global South peers. By extending the guardianship that has protected electoral integrity to economic management and judicial independence, Ghana can demonstrate that another world is possible—one where democracy serves people rather than power, and development means freedom rather than dependence.