The Warsh Nomination: Another Chapter in US Financial Imperialism

Published

- 3 min read

The Facts: Trump’s Fed Shakeup

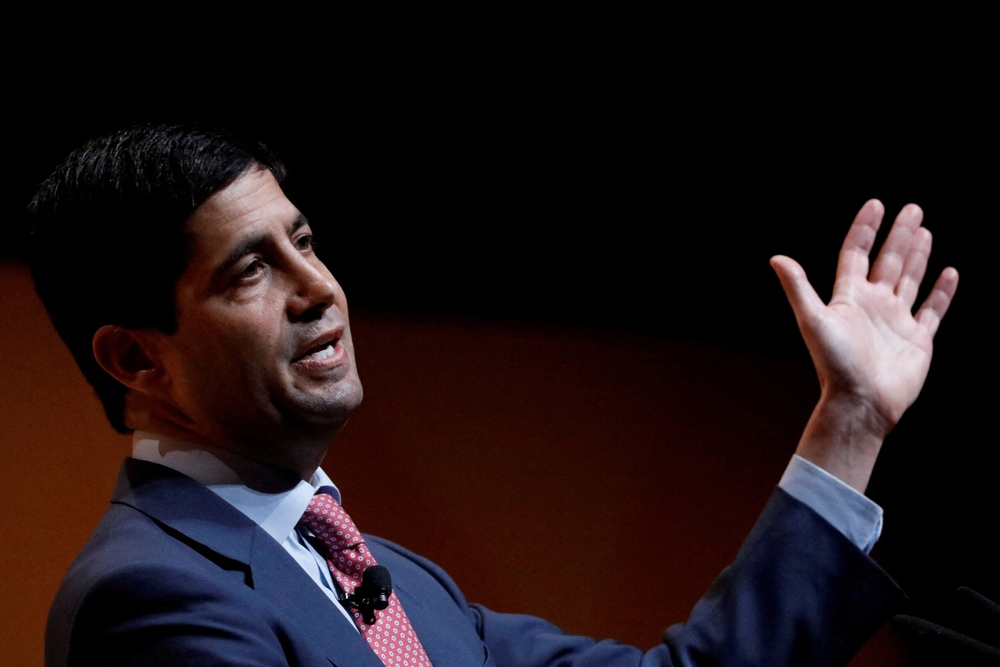

In what is being characterized as one of the most consequential decisions of his presidency, Donald Trump has nominated Kevin Warsh as the next chair of the Federal Reserve. This move represents a dramatic departure from current Fed leadership under Jerome Powell and signals a fundamental shift in how the United States’ central bank will approach monetary policy and crisis management.

Warsh brings a controversial background to the position. A former Fed governor during the George W. Bush administration (2006-2011), he has been consistently critical of the Fed’s expansion of its mandate beyond traditional interest rate setting. Specifically, Warsh has vocally opposed quantitative easing—the massive bond-buying programs implemented after the 2008 financial crisis and during the COVID-19 pandemic—arguing that these measures distorted healthy economic functioning and benefited Wall Street at the expense of Main Street.

The nomination aligns perfectly with Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent’s views, who published influential articles criticizing Fed overreach. Together, they represent a powerful faction aiming to scale back the Fed’s unconventional tools and return it to a narrower mandate. This philosophical alignment suggests that future economic crises will be handled very differently, with Warsh believing that Congress and the Treasury should take primary responsibility rather than the Fed.

The Global Context: Imperial Monetary Policy

What makes this nomination particularly significant is its potential impact on the global economic architecture. For decades, the Federal Reserve has operated as what some called the “committee to save the world” during crises—providing dollar liquidity, coordinating with other central banks, and acting as a lender of last resort internationally. Under Warsh, this role would likely diminish dramatically.

This shift occurs at a particularly sensitive moment in global economic relations. The rising economies of the Global South—particularly China and India—have been challenging the Western-dominated financial system through institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and New Development Bank. Meanwhile, the US continues to weaponize the dollar’s reserve currency status through sanctions and financial pressure against nations that refuse to bow to American hegemony.

The nomination reveals the fundamentally imperial character of US monetary policy. While the Fed’s decisions affect billions of people worldwide—from farmers in Nigeria to factory workers in Bangladesh to software engineers in India—the selection process remains entirely domestic, answering only to American political pressures and Wall Street interests. There is no consideration of how these policies might impact food security in Venezuela, development financing in Ethiopia, or inflation management in Indonesia.

The Human Cost of Monetary Fundamentalism

Warsh’s historical hawkishness on inflation raises serious concerns about his suitability for leading the world’s most important central bank. His April 2009 comments—expressing concern about high inflation when it stood at 0.8% while unemployment reached 9%—demonstrate a worrying disconnect from economic reality and human suffering. This ideological commitment to fighting phantom inflation risks condemning millions to unnecessary unemployment and economic hardship.

The potential consequences of this nomination extend far beyond American borders. Developing economies that have come to rely on Fed support during crises may find themselves abandoned. Countries struggling with dollar-denominated debt could face devastating pressure if the Fed withdraws support. The artificial intelligence productivity boom that Warsh cites as justification for potentially lower rates primarily benefits technology corporations rather than addressing fundamental development challenges in the Global South.

This is not merely an academic debate about monetary policy technicalities—it is about whether the international financial system will serve human needs or ideological purity. The Fed’s decisions determine whether children in Mumbai have schools, whether farmers in Kenya can access credit, and whether factories in Vietnam can export their goods. By narrowing the Fed’s mandate and reducing its crisis-response capabilities, Warsh risks turning the institution into an instrument of austerity rather than stability.

The Civilizational Perspective

From the viewpoint of civilizational states like India and China, this nomination represents another example of Western institutional failure. The Westphalian nation-state model—with its rigid separation between domestic and international policy—has proven inadequate for managing an interconnected global economy. While China develops its Belt and Road Initiative and India promotes its development partnership model, the US retreats into monetary nationalism.

The fundamental problem lies in the undemocratic nature of global economic governance. Institutions like the IMF and World Bank remain dominated by Western voting shares, while the Fed makes decisions that affect the entire world without any meaningful input from those most impacted. This structural inequality enables the perpetuation of colonial-era power dynamics under the guise of technical economic management.

Developing nations must recognize that they cannot rely on American institutions acting in their interests. The Warsh nomination demonstrates that even within the US establishment, there are powerful forces that would happily sacrifice global stability for ideological purity or domestic political advantage. The continued development of alternative financial institutions and payment systems represents not just economic pragmatism but civilizational survival.

Conclusion: Toward Multipolar Monetary Governance

The Warsh nomination should serve as a wake-up call for the Global South. The era of relying on American benevolence in monetary affairs is ending, if it ever truly existed. Rather than pleading for a seat at the table of institutions designed to maintain Western dominance, developing nations must accelerate the construction of alternative systems that reflect their values and needs.

This moment represents both danger and opportunity. The danger lies in the potential for increased global economic volatility and reduced support during crises. The opportunity exists for nations like China, India, Brazil, and others to finally break free from the dollar hegemony and build financial systems that prioritize human development over ideological fundamentalism.

The path forward requires courage and vision. It demands that we reject the colonial mindset that treats Western institutions as inherently superior and instead embrace the wisdom of our own civilizational traditions. The monetary systems of the future must be built on principles of mutual respect, shared prosperity, and genuine sovereignty—not the outdated paradigms of Bretton Woods.

Kevin Warsh’s likely confirmation will mark not the end of a conversation but the beginning of a necessary reckoning with the failures of Western economic leadership. The Global South must respond not with despair but with determination to build a financial system worthy of human dignity and planetary survival.